If you’re relocating to Switzerland, health insurance isn’t just a box‑ticking exercise. Switzerland has compulsory basic cover rules (KVG/LAMal) for people who become resident (and for some work-based cross-border categories), plus defined cost-sharing that can materially affect what you pay yourself over the year.[1][5]

The real question is rarely “Do I need insurance?” It’s “What cover structure will still work in three, five, or ten years—if our plans change, we travel more than expected, or a new medical condition develops?” Switzerland’s system can work well once you understand it, but it rewards early decisions: enrolment timing, your franchise (annual deductible), and whether it makes sense to add supplementary cover and/or IPMI.

This guide explains Swiss health insurance in practical terms: the compulsory foundation (KVG/LAMal), how enrolment works in day-to-day reality, what basic cover includes, how supplementary plans differ, and where expatriate insurance (IPMI) can fit—particularly for globally mobile families.

House note (compliance-safe): Eligibility, deadlines, exemptions and processes can vary by residency status, canton and personal circumstances. Always check with the Swiss authorities and rely on the official policy wording.[1][13]

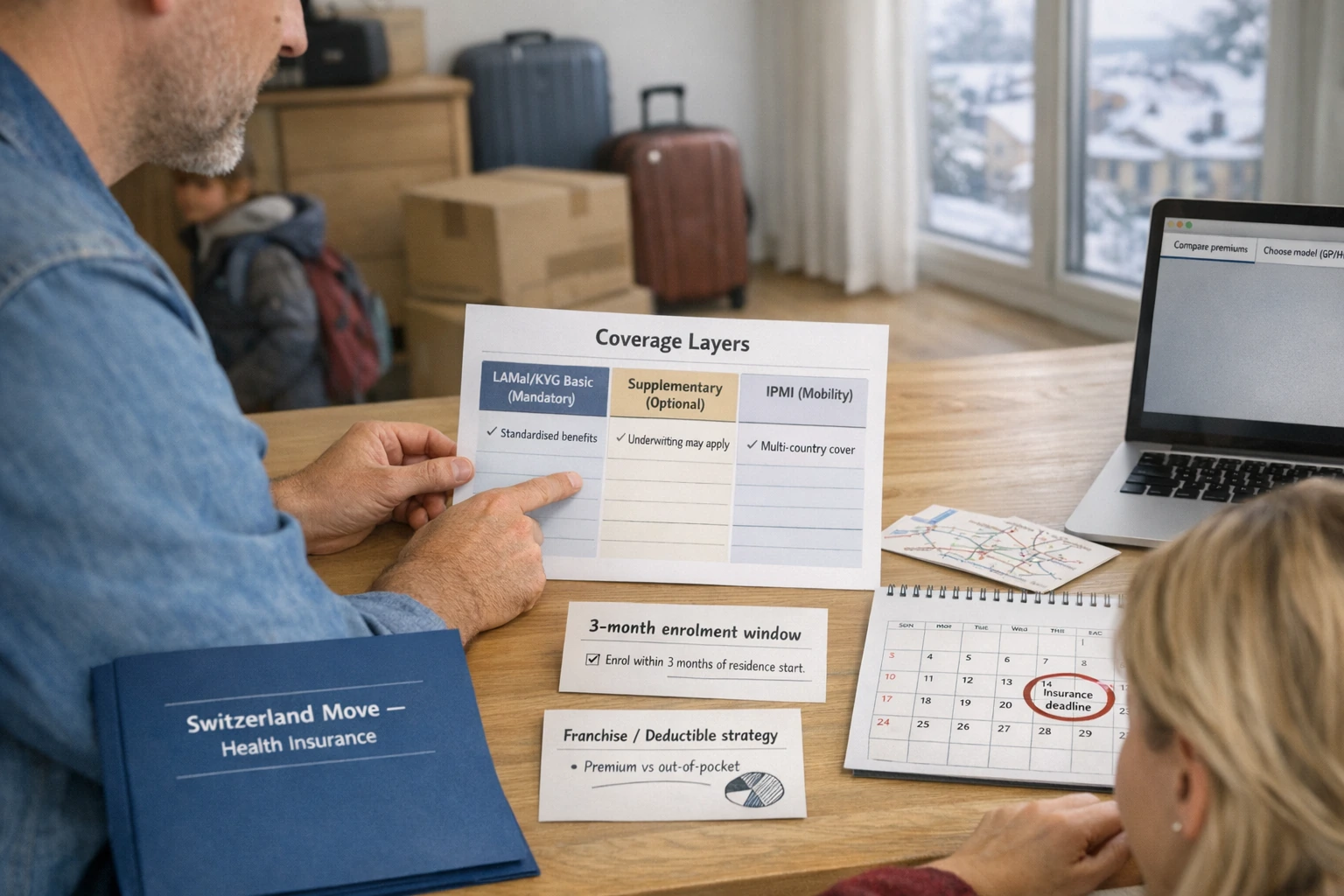

- Start with your status: Most residents must take out Swiss compulsory basic insurance within three months; some cross-border, student or posted-worker situations follow different rules and can require formal exemption steps.[1][13][15]

- Don’t miss the three‑month window: If you enrol on time, cover can be dated from your start date; late registration can mean a later effective date and possible surcharges (and in cross-border cases, you may be liable for costs incurred before enrolment).[1][13]

- Budget beyond premiums: Your franchise (deductible), co-payment (retention fee/co-insurance), and hospital daily contribution can drive real out-of-pocket spend—not just your monthly premium.[5][6]

- Basic benefits are standardised: Every insurer must offer the same legally defined KVG/LAMal benefit package—so you compare price, model, and administration/service experience, not “better basic benefits”.[4]

- Supplementary is optional and underwritten: Supplementary insurance can be declined, can include exclusions, and typically requires a health questionnaire—so timing and disclosure matter.[2][7]

- IPMI can support mobility: If you expect multi-country living or significant travel, IPMI may help with portability and service access—but it typically won’t replace Swiss compulsory requirements once you’re subject to KVG/LAMal.[12][1][24]

- Think in a 3–10 year horizon: Design for change: job moves, canton changes, pregnancy/children, ongoing care, and (for many expats) a possible return home. The right structure is the one that holds up under pressure.[5][11]

Who must enrol in Swiss mandatory basic health insurance (LAMal/KVG)

For most expats, the position is fairly clear: if you become resident in Switzerland, you are generally required to take out Swiss compulsory basic health insurance (KVG/LAMal) within three months of taking up residence.[1] The system is sometimes described as “compulsory, but private”: cover is required, but it is provided by approved insurers within a regulated legal framework.[3]

Two practical points matter straight away for families: each family member must be insured individually, and your timing can affect whether your cover is dated from your start date (and whether eligible costs are reimbursed retrospectively).[1]

- KVG / LAMal: The legal framework for Switzerland’s compulsory basic health insurance (OKP). Most residents subject to compulsory insurance must take it out within three months.[1]

- OKP (basic insurance): Compulsory basic cover. Core benefits are set by law and are the same across all insurers offering basic insurance.[4]

- Franchise / deductible: The fixed annual amount you pay before most benefits are paid (standard deductible is CHF 300 for adults; higher optional deductibles can reduce premiums).[5][9]

- Retention fee / co-payment (Selbstbehalt): Typically 10% of costs above the deductible, up to an annual cap; a separate hospital daily contribution can also apply in many cases.[5][6]

- Insurance models (standard / GP / HMO / Telmed): In basic insurance, you can often choose a model that affects how you access care (for example, GP-first or telemedicine-first) and may affect premiums.[7][2]

- Supplementary cover (Zusatzversicherung): Optional, privately underwritten cover for benefits beyond basic (for example, additional comfort, dental, travel add-ons). Insurers can decline supplementary applications and may apply exclusions.[2][7]

- IPMI (International Private Medical Insurance): International expatriate insurance designed for multi-country living, often with broader geography and service support than local-only systems. Terms vary and underwriting is common.[24]

- Network / direct billing / pre-authorisation: Common IPMI mechanics. Networks can influence whether the insurer pays providers directly, and some planned hospital treatment may require approval in advance.[26]

Terminology can vary by language and insurer. Always cross-check against your policy wording.

| Coverage layer | Best for | Eligibility triggers | Typical strengths | Typical limitations/risks | Portability | Admin complexity | What to verify |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KVG/LAMal basic (mandatory) | Settling in Switzerland with Switzerland-centred care needs | Taking up Swiss residence (and some work-status cases); generally a three-month enrolment window | Standardised benefit package set by law; equal treatment rules; premium models available (standard/GP/HMO/Telmed) [4][7] | Meaningful cost-sharing (deductible + co-payment + hospital daily contribution); limited non-emergency cover abroad; premiums can vary by canton/region/model [5][12] | Primarily Switzerland-centred; limited emergency reimbursement abroad, with specific caps outside the EU/EFTA/UK[12] | Medium: choosing an insurer/model, managing bills/claims, annual reviews | Your obligation start date; your canton’s process; deductible strategy; accident cover coordination; switching deadlines [1][2] |

| Swiss supplementary (optional) | Adding comfort or extra services beyond basic (e.g., additional hospital options, dental, travel extensions) | Voluntary purchase; typically requires a health questionnaire; acceptance not guaranteed | Can extend benefits beyond basic; can be held with a different insurer from your basic plan [2][20] | Underwriting, exclusions and any waiting periods are product-specific; cancellation terms can differ from basic (private contract) [2][21] | Usually Switzerland-focused; some policies include limited travel benefits (verify) | Medium–High: multiple contracts, different terms, potential coordination questions | Underwriting questions; exclusions; waiting period language; renewal and cancellation terms; coordination with basic; discounts/fees if you split insurers [2][20][21] |

| IPMI (international expatriate insurance) | Multi-country living, frequent travel, or a continuity layer across relocations | Voluntary purchase; underwriting is common; may be arranged via employer or individually | Portability; often broader geographic cover; service model may include networks, assistance and direct billing in certain settings [24][26] | May not meet Swiss compulsory requirements once you are subject to KVG/LAMal; exclusions/medical underwriting; cost can be higher for wider geographic areas [1][24] | High by design (multi-country), but geography and renewal terms vary | Medium–High: pre-authorisations, networks, claims routes, coordination with local systems | Whether it can sit alongside Swiss requirements; geography; pre-existing condition terms; provider network strength in your likely locations; renewal mechanics [15][24] |

The baseline rule for residents

The Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) explains that anyone settling in Switzerland must take out health insurance within three months of taking up residence. If insurance is obtained on time, cover takes effect from the beginning of residence and costs incurred since that start date can be reimbursed retrospectively (with premiums payable from that date as well).[1]

ch.ch (official life-in-Switzerland guidance) sets out the same principle in plain language: if you have moved to Switzerland, you have three months to arrange health insurance cover. The same deadline applies to newborns; you or your baby are already covered during this three-month period.[2]

Where the answer can vary (common expat profiles)

Expect compulsory basic insurance within three months. Each family member needs their own policy. If you enrol on time, cover can be dated from your start date. [1]

As a rule, people resident abroad who work in Switzerland are required to take out Swiss health insurance, with limited exceptions and “option” procedures in certain corridors that must be exercised formally and on time. [13]

Posted workers are typically subject to home-country social security legislation. Some EU/EFTA/UK postings of up to two years can be exempted with an A1 certificate; other cases depend on agreements and equivalent cover requirements. [14]

Foreign students can apply for an exemption if they have equivalent cover. EU/EFTA/UK students who are not working may rely on EHIC rules; non-EU/EFTA/UK students can be exempted for three years (extendable by another three), then must take Swiss insurance. [15]

Start and end of compulsory insurance (why this matters for a 3–10 year plan)

The FOPH explains that compulsory insurance essentially applies to people resident in Switzerland, and that cover ceases when you are no longer subject to compulsory insurance—such as when you leave Switzerland to take up residence in another country (with exceptions under certain international agreements).[1]

Over a three-to-ten-year horizon, this is why you should plan your likely “exit route” as well as your arrival: if you leave Switzerland in year three, five or ten, your next system may not start on the same day unless you plan for overlap and proof requirements.

How and when to enrol

The Swiss enrolment process is straightforward, but it is time-sensitive. You typically have a three-month window from the start of compulsory insurance—often from the date you take up residence—to take out basic insurance.[1] Leaving it until “later” is how families end up with avoidable stress, cost, or a compliance headache.

What enrolment looks like in practice

It helps to think about enrolment as three parallel tracks: (1) registering with your commune, (2) confirming your insurance obligation and putting cover in place, and (3) coordinating with employment-related insurance (particularly accident cover).

- Step 1 — Register your arrival: ch.ch guidance for people working in Switzerland notes you must register with the communal authorities where you live within 14 days of arrival (and, in that context, you can’t start work before then).[3]

- Step 2 — Confirm your “start date”: Work out when you became subject to compulsory insurance (residence start, or employment start for some cross-border situations).[1][13]

- Step 3 — Choose a basic insurer: You can choose an authorised insurer operating in your region. The supervisory authority publishes directories of approved health insurers.[16]

- Step 4 — Choose model + deductible: Decide whether you want the standard model (free choice) or a reduced-premium model (GP/HMO/Telmed), and choose your franchise/deductible with a “total annual cost” mindset.[7][9]

- Step 5 — Coordinate accident cover: In accident cases, the health insurer steps in only if you have no other coverage; if you work more than eight hours a week, your employer is generally obliged to insure you for accidents.[4][3]

- Step 6 — Keep proof: Keep your policy confirmation and effective date. If you enrol on time, cover can be dated from your start date; if you enrol late, cover may only start from the enrolment date and you may face a surcharge unless the delay is justified.[1]

This is a planning framework. Cantonal processes and exact proof requirements can differ. Verify locally where needed.

If you enrol late (why effective dates matter)

The FOPH draws a clear distinction between enrolling within the legal period and enrolling late: enrol on time and cover can begin from your start date (with reimbursement of eligible costs incurred since then, and premiums due from that date). Enrol late and cover generally only takes effect from the date you enrol, with a surcharge unless the delay is justified.[1]

For cross-border commuters, the FOPH is particularly explicit: not registering can lead to automatic assignment to an insurer and (if the delay can’t be justified) a premium surcharge—while you may have to pay treatment costs incurred prior to enrolment yourself.[13]

First 90 days timeline (and the 3–10 year lens)

- Identify your likely status: resident, cross-border commuter, posted worker, student (these can change the rules and deadlines).[1][13][15]

- Build a “don’t cancel too early” plan for existing cover (particularly if travel or relocation steps overlap).

- If your first entry is via Schengen short-stay visa steps, note that SEM sets a travel medical insurance requirement (up to EUR 30,000 for emergency treatment and repatriation risk) for Schengen visa applicants. This is separate from Swiss KVG/LAMal rules for residents.[19]

- Day 30: Choose insurer + model + deductible; submit the application and keep written confirmation.[7][9]

- Day 60: Confirm accident insurance coordination (particularly if employed >8 hours/week).[3][4]

- Day 60: If you’re seeking an exemption (student/posting/cross-border option), submit within the stated timelines to the relevant cantonal authority and keep the decision in writing.[13][14][15]

- Day 90: Ensure compulsory cover is active and the effective dates align with your circumstances; address any gaps straight away.[1]

- Compare premiums and models using Priminfo (premiums are approved and published by the FOPH).[10]

- Switch basic insurer/model if needed: ch.ch states your cancellation letter must reach your insurer by 30 November for year-end switching (and notes certain mid-year cancellation possibilities in defined cases).[2]

- Check whether premium subsidies may apply; eligibility and process are set by each canton.[11]

- Re-check your structure when you change canton, change employer, start a family, increase travel, or plan to leave Switzerland.[5][12]

- Set an annual reminder for a “total cost” review: premium + expected out-of-pocket + travel exposure.

- Don’t assume today’s plan will be easy to replace later: supplementary and IPMI often involve underwriting and exclusions (acceptance is not guaranteed).[2][24]

Common pitfalls (what tends to cost expat families the most)

- Missing the three-month enrolment deadline: enrolling within the deadline can mean cover is dated from your start date; late enrolment can affect effective dates and may trigger surcharges (and in cross-border cases can leave you paying earlier costs yourself).[1][13]

- Assuming your employer enrols you into basic insurance: ch.ch emphasises that health insurance is compulsory but private—meaning you normally arrange it yourself, even if you are working.[3]

- Choosing the franchise/deductible based on premium alone: co-payment is structured (deductible + 10% retention fee up to a cap + hospital daily contribution). Your out-of-pocket exposure can still be meaningful even where the monthly premium looks low.[5][6]

- Mixing up basic and supplementary insurance: supplementary is optional and can be declined; it usually requires a health questionnaire and can include exclusions—unlike basic insurance acceptance rules.[7][2]

- Paying twice for accident risk (or being uninsured for accidents): accident cover often depends on employment status; above an eight-hour/week threshold, your employer is generally obliged to provide accident insurance.[3][4]

- Overlooking the “abroad gap”: outside the EU/EFTA/UK, emergency reimbursement is capped (up to twice the Swiss amount; inpatient reimbursement no more than 90% of comparable Swiss hospitalisation costs). In high-cost countries, basic insurance may be insufficient.[12]

- Cancelling old cover too early: the gap risk is often administrative, not just medical. Build in overlap until the new structure is confirmed and effective.

Switching note: ch.ch states basic insurance can generally be changed at year-end if your written cancellation reaches your insurer by 30 November. It also describes a mid-year cancellation option in specific circumstances (for example, the standard model with a CHF 300 deductible, with three months’ notice). Always check your specific situation and contract terms.[2]

What basic cover includes

Swiss compulsory basic insurance (KVG/LAMal) provides a legally defined set of benefits. The FOPH summarises these benefits as cover for illness, accident and maternity, including examinations and treatment from doctors and in hospital, nursing and some non-medical services, plus medical prevention measures.[4]

A key system point: insurers that offer compulsory basic insurance must offer the same scope of benefits as mandated by law and must ensure equal treatment of insured persons; they are not allowed to include additional “voluntary” services within the basic package.[4]

Cost-sharing in plain English (premium vs what you pay yourself)

In Switzerland, your monthly premium is only part of the picture. The FOPH explains that co-payment generally includes: a deductible (standard CHF 300 for adults; children under 18 are exempt from the standard deductible), a retention fee of 10% of costs above the deductible up to a maximum (CHF 700 for adults; CHF 350 for children/adolescents), and a CHF 15/day contribution for hospital stays, with exemptions for certain groups (including children/adolescents and maternity services).[5][6]

ch.ch notes that if you choose the highest deductible, you should still plan to have at least CHF 3,200 set aside (deductible + maximum retention fee) in case you become ill—before allowing for the hospital daily contribution or non-covered costs.[17]

This is a budgeting illustration, not advice. Your actual out-of-pocket will depend on your chosen deductible, the care you use, and which cost-sharing rules apply in your circumstances.[5]

Premiums: why they vary (and what you can meaningfully compare)

The FOPH explains that insurers set premiums and (unless the law says otherwise) broadly charge the same premiums for policyholders, but premium levels vary based on cost differences within cantons and depend on where you live. Insurers may also charge different premiums for different regions (with standard premium regions defined by the FOPH), and premiums are payable in advance, usually monthly.[5]

Premiums for compulsory health insurance are approved and published by the FOPH, and the official premium overview/calculator is available via Priminfo.[10] If you’re comparing options, compare like-for-like (same canton/region, age group, model and deductible).

If you are in modest economic circumstances, premium reductions may be available. The FOPH explains that cantons reduce premiums for eligible residents and each canton sets eligibility, process and payment arrangements (some require an application; others may grant reductions automatically).[11]

Insurance models: standard vs GP/HMO/Telmed

Basic insurance is often offered under different “models” that can affect how you access care. Alongside the standard model (free choice), the FOPH describes common reduced-premium models such as GP (family doctor), HMO and Telmed models.[7] ch.ch explains these in practical terms and notes model changes are typically aligned with year-end switching deadlines.[2]

The broader logic is also described by the FOPH: you can reduce premiums by limiting the choice of provider in agreement with the insurer, by choosing a higher deductible, or via bonus insurance structures (availability can vary, and special types may not be available to all categories such as policyholders resident in EU/EFTA/UK corridors).[8]

Accidents: coordinating health and accident insurance

Basic insurance provides benefits in the case of accident, but the FOPH notes that the health insurer steps in only if the insured person has no other coverage.[4] ch.ch explains that if you work more than eight hours per week, your employer is obliged to insure you for accidents (with the contribution deducted from salary). If you work less than eight hours a week, you may need private accident insurance.[3]

Care outside Switzerland (and why expats should check this early)

Many expats only discover late that “abroad” rules are specific. The FOPH explains that: within the EU/EFTA/UK, the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) entitles medically necessary treatment during a stay, with co-payment based on the country of treatment and generally payable directly; those amounts generally do not count towards your Swiss deductible/retention fee.[12]

For temporary stays outside the EU/EFTA/UK, the FOPH states that emergency treatment costs will be reimbursed up to a maximum of twice what the insurer would have paid for treatment in Switzerland, and for inpatient treatment the insurer will reimburse no more than 90% of comparable Swiss hospitalisation costs. It also notes that medical costs can be very high in some non-EU/EFTA/UK countries (for example, the US, Canada and Japan) and basic insurance benefits may be insufficient to cover the costs; other medical treatment abroad is not generally covered under compulsory insurance.[12]

This is one of the main reasons expats explore supplementary “abroad” extensions or IPMI—especially if they expect frequent travel or future relocations. Always verify the geography, reimbursement method and any caps in writing before relying on them.[12]

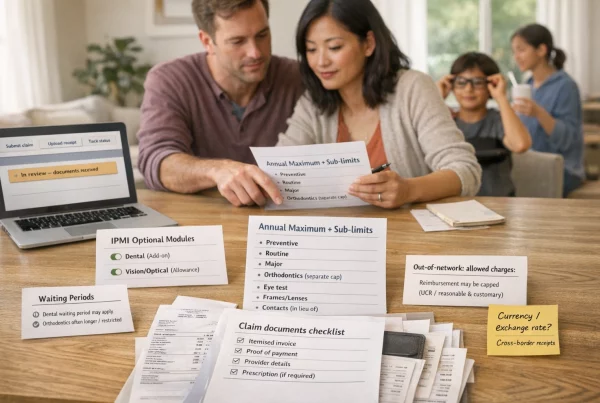

Private supplementary plans

In Switzerland, “public vs private” is an easy shorthand, but it can be misleading. It’s often clearer to think in layers: compulsory basic insurance (standardised benefits) plus optional private supplementary insurance for additional benefits and comfort. Supplementary cover can be useful, but it is governed by different rules from basic insurance.

What supplementary insurance is (and what it isn’t)

The FOPH’s FAQs explain the distinction: basic insurance is compulsory and insurers must accept everyone subject to compulsory insurance without reservation or waiting period, regardless of age and state of health. Supplementary insurance is different—insurers may refuse to insure you after a health check or exclude you from certain benefits.[7]

At a high level, supplementary insurance can cover services not included in basic insurance. The FOPH’s FAQ gives examples such as semi-private/private hospital wards, routine dental treatment, preventive check-ups, and treatment by naturopaths (examples vary by product and insurer).[7]

Underwriting, exclusions, and “waiting periods” (what to expect)

ch.ch is very clear on the practical reality: as a rule, you have to complete a health questionnaire before an insurer approves supplementary insurance, and the insurer can refuse the application. It also warns that you should answer the questionnaire truthfully, because incorrect information can lead to bills not being paid later or cover being cancelled.[2]

Some supplementary policies can also include staged benefits or waiting periods for certain categories (product-specific). That’s why you should request the full terms and check effective dates and exclusions before assuming a benefit is available from day one.

Regulatory split: why supplementary behaves differently

FINMA explains that health insurance is regulated by two separate bodies: the FOPH is responsible for compulsory health insurance, while FINMA is responsible for supplementary health insurance under the Insurance Contract Act. FINMA also notes that basic and supplementary insurance are separate contracts and can be taken out independently.[20]

Cancellation terms: why supplementary isn’t always “calendar-year simple”

FINMA highlights that supplementary insurance is private insurance and the contract terms matter. It notes that, following the revision of the Insurance Contract Act, policyholders can cancel their supplementary contract in writing after three years with three months’ notice to the end of the insurance year, even if a longer term was originally agreed. It also notes that the insurance year does not necessarily end on 31 December—your contract documentation is what counts.[21]

Coordination choices: same insurer or split?

Both ch.ch and FINMA confirm you can hold compulsory basic insurance and voluntary supplementary insurance with different insurers.[2][20] FINMA notes a trade-off: having two providers can mean you need to be clear about who handles which costs, but the ability to switch basic insurance to a cheaper provider may be financially helpful.[20]

FINMA also highlights a point many expats miss: some providers may only offer discounts on supplementary insurance if you also hold basic insurance with them, and they may charge administration fees or apply minimum premiums if you no longer hold basic insurance with them. It’s sensible to ask about this before splitting providers.[20]

Often focused on additional hospital comfort or services beyond the compulsory package. Check how this coordinates with your canton and your chosen model.

Basic insurance isn’t designed to include many “add-on” categories. Supplementary can sometimes cover these, but acceptance is not guaranteed and terms vary.[7]

Some supplementary structures are marketed to reduce the “abroad reimbursement gap”. Always check geography, emergency definitions and whether this fits your travel profile.[12]

- Underwriting approach: health questionnaire, acceptance rules, and potential exclusions.[2]

- Effective date and any waiting/staged benefits: what is covered now vs later, if applicable.

- Cancellation and renewal terms: note that the insurance year-end may not be 31 December in every contract.[21]

- Coordination with your basic insurer: administration, claim routing, and whether discounts/fees apply if you split insurers.[20]

- Travel and abroad benefits: verify caps, reimbursement method, and “emergency” definitions—especially outside the EU/EFTA/UK where basic reimbursement is limited.[12]

IPMI vs Swiss plans

IPMI (international private medical insurance) is generally a mobility-first product category—designed for people living and working across borders. Mercer describes IPMI as international health coverage that can be valid across multiple countries and designed to provide comprehensive coverage, unlike local health insurance designed for a local healthcare environment.[24]

That can make IPMI a good fit for some expats—but it can also create confusion in Switzerland, where you may still be required to take out Swiss compulsory basic insurance once you become subject to KVG/LAMal rules.[1]

A simple way to compare (systems, not brochures)

It helps to compare what each layer is designed to do: Swiss basic insurance is a regulated foundation for Switzerland-centred care, with defined cost-sharing and standardised benefits across insurers. Supplementary is an optional layer under private contract rules. IPMI is a cross-border continuity tool that can be strong for mobility and travel exposure—but it should not be assumed to replace Swiss compulsory obligations.[4][20][24]

How IPMI typically works in practice (service model)

Many IPMI plans are built around provider networks and settlement routes (direct billing vs reimbursement), with pre-authorisation requirements for planned hospital treatment. BIG’s explainer on direct billing vs reimbursement highlights that networks and approvals can determine whether you can access cashless treatment or whether you’ll need to pay up front and claim back.[26]

For globally mobile families, this matters because the “worst day” scenario is often a large hospital bill in a country where you don’t have a smooth billing pathway. If your life involves high-cost countries or multiple relocations, how you use the plan can be as important as what the brochure lists.

Where IPMI can fit alongside Switzerland (typical fit patterns)

If you expect to relocate again within three to five years (or spend significant time abroad), IPMI can provide continuity across borders—subject to underwriting and the policy’s geography/renewal terms.[24]

Swiss basic insurance has defined reimbursement limits outside the EU/EFTA/UK for emergency treatment, and it highlights high-cost countries where basic benefits may be insufficient. A mobility layer can reduce “rare but severe” exposure—if structured correctly.[12]

During transition phases (multiple moves, temporary living arrangements, cross-border family splits), an international solution may help reduce gaps—while you still verify Swiss compulsory requirements and timelines.[1]

Where IPMI usually does not replace Swiss compulsory insurance

The default rule for residents remains: anyone settling in Switzerland must take out health insurance within three months of taking up residence.[1] Exemptions exist in certain categories (for example, some students with equivalent cover, posted worker cases, cross-border “option” procedures), but these typically involve formal steps with cantonal authorities and equivalence requirements.[15][14][13]

Treat IPMI as a potential layer (mobility, abroad exposure, service support) rather than assuming it replaces Swiss KVG/LAMal obligations. If your plan is to rely on non-Swiss cover instead of Swiss basic, verify whether an exemption applies to your exact status, and how equivalence is assessed and documented in your canton.[13][15]

How to decide (a calm decision framework)

Instead of asking “public vs private”, ask questions that still make sense in a few years’ time:

- Will most of your care be Switzerland-centred (GP, paediatrics, routine care), or do you expect multi-country treatment?

- How often will you be outside the EU/EFTA/UK—and which countries? (Basic reimbursement caps outside the EU/EFTA/UK can be material.)[12]

- Are you optimising for the lowest monthly premium or the lowest total cost (premium + expected out-of-pocket + travel risk)?[5]

- If a new medical condition develops, would you regret having to go through new underwriting to add supplementary cover or IPMI later?[2]

Long-term strategy (cross-border living, return to home country)

The costliest insurance decisions are often made under time pressure. A calmer approach is to treat your move in phases: (1) compliance and enrolment, (2) arrival logistics and real-world access to care, and (3) a longer-term structure that still works when your life changes.

Three horizons: 3-year / 5-year / 10-year thinking

Cross-border living and commuting (high-level)

If you live outside Switzerland and work in Switzerland, the FOPH states that you are generally required to take out Swiss health insurance, with some exceptions depending on country of residence and nationality. It also notes that EU/EFTA/UK cross-border commuters (G permit holders) are subject to compulsory insurance from the start of employment, with three months to register.[13]

The FOPH also explains that Switzerland has agreements with neighbouring countries so that people with EU citizenship living in certain neighbouring countries can have an option to obtain insurance in the country of residence—but this is procedural and must be exercised formally within three months by applying to the relevant cantonal authority. It also references case law indicating that “tacit” exercise of the option does not have legal force, so formal steps matter.[13]

ch.ch similarly summarises the cross-border approach: as a cross-border commuter, you may have the choice of taking out health insurance where you work (Switzerland) or where you live, and if you do not want Swiss health insurance you must apply for an exemption with the relevant cantonal authority within three months of starting your job.[2]

Return to home country (and “don’t cancel too early” logic)

The FOPH explains that cover ceases when you leave Switzerland to take up residence in another country, unless an international agreement requires you to remain insured in Switzerland.[1] In practice, that means your return plan should be structured like a handover: confirm your new cover and effective date before terminating Swiss cover, and plan for common proof needs (policy certificates, effective dates, prior coverage confirmations).

Budget planning: Switzerland is high-cost (why cost-sharing strategy matters)

Switzerland is a high-cost healthcare environment. The MonAM health cost indicator (FOPH/Obsan) reports estimated 2024 healthcare costs of CHF 97.1 billion, around CHF 10,783 per capita, representing 11.8% of GDP.[22] In that context, relatively small plan-structure choices (deductible level, model, supplementary layering) can have a noticeable impact on predictable budgeting.

This is not a reason to “buy everything”. It’s a reason to map your total exposure and keep the ability to adapt as your circumstances change.

Annual optimisation without self-sabotage

- Compare premiums properly: premiums are approved/published by the FOPH; use Priminfo for official comparisons.[10]

- Track switching deadlines: ch.ch states cancellation must reach your insurer by 30 November for year-end switching and notes model-change timing is similar.[2]

- Deductible changes are calendar-year decisions: the FOPH notes deductible changes take effect at the beginning of the calendar year, and insurers are not required to offer every deductible level.[9]

- Don’t assume supplementary will be available later: underwriting and acceptance risk is real.[7]

Checklists for registration and arrival

Use the checklists below as a practical project plan. They are deliberately general because Swiss processes can vary by canton, commune and status. If your situation is non-standard (cross-border commuter, posted worker, student exemption), treat “verify with the relevant authority” as a required step, not a footnote.[13][15]

Arrival admin checklist (first two weeks)

- Register with your commune (commonly within 14 days in work contexts).[3]

- Set up a “Swiss admin folder” (digital + printed) for: ID, address proof, employment proof, health insurance confirmations, and correspondence.

- Confirm whether you are subject to compulsory health insurance (resident vs student/posting/cross-border status).[1][15][14]

- Start basic insurance selection early; don’t leave it until day 80+ of your three-month window.[1]

Basic insurance setup checklist (first 30–60 days)

- Choose your basic insurer from approved providers (directory published by the supervisory authority).[16]

- Choose your model (standard vs GP/HMO/Telmed).[7]

- Choose your franchise/deductible level and plan your “worst reasonable year” out-of-pocket budget.[5][17]

- Coordinate accident cover (particularly if employed >8 hours/week).[3][4]

- Save proof of enrolment and effective date; understand backdating/effective date rules and premium payment expectations (premiums are payable in advance, usually monthly).[1][5]

- Set a calendar reminder for October/November (premium updates and any switching decision).[2]

Documents/proof commonly requested (not a definitive list)

Requirements vary. Think in categories and bring originals where possible. ch.ch examples for work-related residence steps include a valid ID/passport and employment confirmation/contract.[3] For moving/commune registration, ch.ch suggests documents can include civil status documents (e.g., certificate of origin), a family record document if you have children, and your health insurance card or proof of your current policy.[18]

- Identity: passport or national ID (for each family member).[3]

- Address: rental contract / address confirmation (commune-specific).

- Employment / purpose of stay: employment contract or employer confirmation; for self-employment, evidence you can support yourself and your family (examples listed by ch.ch).[3]

- Health insurance proof: Swiss health insurance card or policy confirmation; if moving between communes, ch.ch includes a health insurance card/proof as an example document to bring.[18]

- Family documents: family record document / family booklet where applicable (commune-specific), plus birth/marriage records as requested.[18]

- Status-specific proof: student enrolment proof and evidence of equivalent cover if applying for exemption;[15] A1 or posting certificates in posted-worker cases;[14] cross-border option forms and cantonal confirmations if relevant.[13]

This list is intentionally non-exhaustive. Your commune/canton may require additional documents, certified copies, or translations.

Continuity checklist: “don’t cancel old cover too early”

- Keep existing cover in place until your Swiss basic insurance is confirmed and you understand effective dates and any backdating implications.[1]

- If you are applying for an exemption (student/posting/cross-border), wait for the written decision and the confirmed equivalence approach before relying on non-Swiss cover.[15][14][13]

- If you will travel outside the EU/EFTA/UK, remember Swiss basic cover has defined reimbursement limits for emergency treatment in non-EU/EFTA/UK countries and does not generally cover other treatment abroad.[12]

- Store proof of prior cover and cancellations carefully (you may need this for future moves or claims).

If you want a lower-stress relocation, treat administration timelines as part of healthcare planning—not an afterthought.

Broker’s role

A broker’s role isn’t to “pick a brand” for you. It’s to help you build a cover structure that is compliant, cost-aware, and still workable over a three-to-ten-year horizon. In Switzerland, that often means reducing avoidable mistakes: missed deadlines, an unsuitable deductible/model, confusion between basic and supplementary cover, and gaps created during a move.

How we typically support expats (practical, not hype)

- Status mapping: help you frame your likely category (resident vs cross-border vs student/posting) and identify where formal verification is needed.[1][13]

- Structure design: LAMal/KVG as the foundation, then evaluate whether supplementary and/or IPMI makes sense for your travel and longer-horizon plans—without assuming you need “more cover”.[7][24]

- Total-cost thinking: help you model premiums + cost-sharing exposure (deductible + co-payment + hospital daily contribution), not premium alone.[5]

- Policy literacy: translate key terms you’ll actually see (franchise/model restrictions, exclusion wording, geography, reimbursement caps).[12]

- Planning for change: annual reviews, relocation planning, and reducing “coverage cliff edges” when moving countries or returning home.[1]

What we cannot do (and shouldn’t promise)

- We cannot change Swiss legal obligations or cantonal procedures.

- We cannot guarantee acceptance into supplementary insurance or IPMI (underwriting rules apply and may vary by insurer and product).[2]

- We cannot guarantee claims outcomes; entitlements depend on policy wording and the specific facts of a claim.

Get Started

If you’re planning a move to Switzerland and you want a calm second opinion on your health insurance structure—LAMal/KVG setup, supplementary considerations, and when IPMI may fit for mobility—we can help you map your situation and reduce avoidable mistakes.

Start here: Individual & Families and, if you’re ready to request options, Get a Quote.

Further reading (strategy mindset): The A to Z Premium Guide to CFE and US Citizens Moving to Italy.

Points to verify

- Who is subject to mandatory LAMal/KVG in your specific situation and the enrolment deadline you must follow (status and canton can matter).[1][13]

- Whether any exemption/alternative coverage options apply (if any) and how to document them (students, posted workers, certain cross-border cases).[15][14][13]

- How franchise/deductible and cost-sharing will apply to your expected care pattern (including retention fee caps and hospital contribution rules).[5][6]

- How supplementary underwriting, waiting periods, exclusions, and acceptance work for your household (varies by insurer and product).[2][7]

- Cross-border living/commuting rules and what they mean for where you can receive care and how it’s reimbursed (especially EU/EFTA/UK vs non-EU/EFTA/UK).[13][12]

- Employer coordination: whether your employer provides accident insurance (>8 hours/week) and how that coordinates with health insurance cover for accidents.[3][4]

- Whether IPMI would be accepted/appropriate alongside Swiss requirements (depends on purpose, status, and equivalence/exemption pathways; do not assume substitution).[1][15]