International private medical insurance (IPMI) can be an important safety net for globally mobile employees. For multinational HR teams, however, the real decision is often how the programme is funded — because funding changes your risk, cash flow, governance duties, reporting visibility and compliance exposure. This guide compares self-funded vs fully insured international health schemes in practical terms, with a focus on stop-loss, claims administration/TPA support, multinational pooling/captives and cross-border regulatory constraints.

If you are considering self-funding, you typically need the basics below in place (or a clear plan to build them):

- Finance and cash-flow planning: agreed reserves approach, funding mechanics and internal controls.

- Actuarial support: credible claims projections, volatility modelling and attachment point analysis.

- Legal and compliance input: jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction permissibility, distribution rules and plan documentation.

- Claims governance: decision rights, escalation routes, audit processes and oversight of suppliers.

- TPA/ASO capability: service scope, global network access, reporting cadence, and operational resilience.

- Data governance: privacy-by-design, access controls and cross-border transfer safeguards for health data.

- Risk transfer vs retention: fully insured plans transfer claims risk to the insurer; self-funded plans retain it. Stop-loss can help manage high-severity claims, but it does not remove risk entirely.

- Cash-flow predictability: fully insured arrangements are premium-based and typically more predictable; self-funded arrangements can be more variable and require funding claims as they arise.

- Data & control: self-funding can provide more detailed claims reporting and more flexibility in plan design; fully insured arrangements may offer less transparency but can reduce operational load.

- Administration: self-funded employers typically rely on TPAs and need stronger governance; insurers usually provide a more “bundled” administration model in fully insured arrangements.

- Jurisdiction matters: self-funding may not be permitted or practical in some countries; cross-border programmes must meet local distribution rules and privacy requirements (e.g. GDPR) and may have different tax/accounting treatment.

- Stop-loss terms matter: attachment points, coverage periods, exclusions and lasers can materially change retained risk — contract review is essential.

- Capability is a decision factor: without the right finance, actuarial, legal and HR ops capability, the risks and friction of self-funding can outweigh the potential advantages.

Definitions of self-funded and fully insured schemes

When you design an international group medical programme, the funding model determines who bears claims risk, how cash flows operate, and which regulatory frameworks may apply. Two broad approaches dominate: self-funded and fully insured. Hybrid approaches (for example, level-funded arrangements and captive programmes) sit between these two ends of the spectrum.

Self-funded health plan (self-insured)

The employer (or association) pays eligible medical claims from its own funds and retains the financial risk. A third-party administrator (TPA) may administer claims and provide network access, but the employer remains responsible for funding claims. [1]

Fully insured plan

The employer purchases a group health insurance policy from an insurer. In return for premium payments, the insurer pays claims in line with policy terms and conditions. [2]

Stop-loss insurance

Cover purchased by a self-funded employer to protect against excessive claims. “Specific” stop-loss responds when an individual claimant’s eligible claims exceed an attachment point; “aggregate” stop-loss responds when total eligible claims exceed a defined threshold. [4]

Third-party administrator (TPA) / Administrative services only (ASO)

A specialist administrator that handles claims processing and related operational services for a plan sponsor. In an ASO model, an insurer may provide administrative services while the employer remains responsible for paying claims. [5]

Multinational pooling

A risk-management arrangement that consolidates results from local employee benefit plans across multiple countries into a single international pool, potentially enabling an international dividend where results are favourable (subject to pooling terms). [7]

Captive programme

A company-owned insurance entity used to underwrite risks for the parent company’s benefit programmes. Captives can be used to consolidate risk and, in some structures, retain underwriting profit, but require capital, specialist governance and regulatory oversight. [8]

Experience rating

A pricing approach where premiums (or projected claims costs) reflect a specific group’s claims experience. In fully insured markets, rating approaches vary by jurisdiction and product; in self-funded arrangements, the employer directly experiences its own claims costs.

Self-funded health plans

In a self-funded plan, the employer pays healthcare claims for employees and dependants directly from corporate funds. A TPA may administer the plan, but the risk of claims — both frequency and severity — sits with the employer. In the US, self-funded arrangements are widely used, particularly among larger employers. [3]

- Risk retention: your organisation funds claims and absorbs volatility.

- Plan design flexibility: benefits, excess/deductible structures and networks can often be tailored (subject to local rules).

- Stop-loss: commonly used to limit exposure to high-severity and/or aggregate claims.

- TPA/ASO: administration is typically outsourced; the employer remains responsible for funding.

Fully insured plans

A fully insured plan transfers claims risk to an insurer. The employer pays a premium, and the insurer pays claims in line with the policy wording. Because the insurer assumes risk, premiums typically include administrative costs and an element for risk. Fully insured arrangements are common where groups are smaller, where risk transfer is preferred, or where self-funding is not permitted or practical. [2]

- Risk transfer: the insurer bears claims risk, subject to policy terms and conditions.

- Administration: insurers typically provide a bundled claims/network administration model.

- Reporting: employers often receive higher-level claims reporting; granular data can be restricted by privacy rules.

Advantages and disadvantages of each

Choosing between self-funding and fully insuring an international health programme generally means balancing financial risk, operational capacity and legal constraints. Outcomes depend on workforce profile, claims experience, plan design and jurisdictional requirements — no model guarantees savings or specific claims outcomes.

| Decision criteria | Self-funded IPMI | Fully insured IPMI |

|---|---|---|

| Who it suits | Medium to large employers with credible claims experience, higher risk tolerance and governance capability | Small to mid-sized employers; organisations prioritising predictable costs; employers in restricted markets |

| Cash-flow | Variable; employer funds claims as they arise (timing and severity can create volatility) | Premium-based; typically more predictable over the contract period |

| Risk | Employer retains claims risk; stop-loss may mitigate but does not remove risk | Risk transferred to insurer, subject to policy wording, exclusions and limits |

| Typical governance needs | Finance/actuarial input, reserve planning, claims oversight, supplier management, stop-loss review | Lower operational burden; insurer provides administration infrastructure (employer still needs oversight) |

| Data requirements | Potential access to more detailed claims reporting (subject to privacy and data minimisation) | Often higher-level reporting; granularity may be restricted by privacy law and insurer policy |

| Speed of change | In some structures, plan design changes can be made mid-year if permitted by plan documents and local rules (and may affect stop-loss) | Changes usually made at renewal and subject to underwriting and local regulatory requirements |

| Cross-border friction | Often requires jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction legal review; local stop-loss/TPA capability may not be available | Insurer infrastructure can help with local compliance, though master policy structures often still need localisation |

| What can go wrong? | Cash-flow shocks; stop-loss gaps/exclusions/lasers; reporting creates privacy risk if governance is weak; disputes on eligibility/reimbursement | Renewal premium increases; limited transparency; less flexibility; service issues or coverage disputes |

- More flexibility in plan design and supplier selection.

- Potentially better visibility of cost drivers through reporting (subject to privacy constraints).

- Ability to align governance and vendor strategy across regions where permitted.

- Higher retained risk and cash-flow volatility, even with stop-loss.

- Greater operational and compliance burden (claims governance, data handling, oversight).

- Stop-loss terms can materially change protection (attachments, exclusions, lasers).

- More predictable premium-based budgeting across the contract period.

- Insurer-led administration and local policy infrastructure.

- Often the practical route where self-funding is restricted.

- Less flexibility and more reliance on renewal cycles for change.

- Less granular reporting in many markets.

- Renewal pricing can move with experience and market trends.

Note: “self-funded” and “fully insured” can look different in practice depending on the country, the policy structure and how administration is delivered. Where the position is unclear, treat it as a point to verify.

Financial risk and stop-loss considerations

If you self-fund, you assume claims liability and need to manage both volatility and timing risk. Stop-loss can help limit exposure to high-severity claims, but it does not turn a self-funded programme into a fully insured one. [4]

What risk you are retaining

Self-funding typically exposes you to: (a) high-severity, low-frequency “shock” claims; and (b) higher utilisation across the group that accumulates into significant total cost. Large claims can occur early in the plan year, and reimbursement (where applicable) can lag behind payment, putting pressure on cash flow.

How stop-loss works in practice

Stop-loss is generally structured around an attachment point (your retained amount) and then reimbursement above that level for eligible claims. Specific stop-loss applies to an individual claimant; aggregate stop-loss applies to total group claims. [4]

- Attachment points: lower attachments typically increase stop-loss cost but reduce retained volatility.

- Coverage period: confirm incurred/paid basis and how “run-off” claims are treated (timing gaps can matter).

- Exclusions: check what is not reimbursable (and whether plan design changes affect eligibility).

- Lasers: some carriers apply higher individual attachments for named high-risk individuals, which increases retained exposure. [6]

- Claims evidence and audit rights: ensure documentation requirements are practical and understood by the administrator.

Multinational pooling and captives (high-level)

For multinationals using local insured policies, multinational pooling can consolidate results across countries into a single international account and may provide an international dividend where results are favourable (subject to pooling rules and performance). [7]

Captive programmes can be used to consolidate risk across benefit lines and geographies, depending on structure, regulation and scale. In practice, captives are most commonly explored by larger organisations with mature risk governance and the capital to support an insurance entity. [8]

Pooling and captive feasibility varies materially by jurisdiction, insurer/administrator capabilities and your own claims credibility. Treat this as a feasibility exercise rather than a default next step.

Administrative complexity and TPA support

Administration is often where self-funding succeeds or struggles. Even where you retain risk, you will usually rely on a TPA (or an insurer under an ASO model) to administer eligibility, claims processing, network access and reporting. TPAs provide operational services, but they do not typically assume your claims risk. [5]

What TPAs/ASO providers typically do

- Claims administration: eligibility checks, adjudication, payment processing and query handling.

- Network access: provider contracting and billing pathways (varies by region).

- Member services: enrolment changes, ID cards, helplines and case management (scope varies).

- Reporting: claims/utilisation reports, trend analysis and (where agreed) dashboards.

| Operational area | Self-funded (with TPA/ASO) | Fully insured |

|---|---|---|

| Claims processing | Employer funds claims; administrator processes claims and pays providers using employer funds | Insurer administers and pays claims; employer pays premiums |

| Vendor management | Employer often coordinates multiple suppliers (TPA/ASO, stop-loss, analytics, wellbeing) | More bundled insurer model (though multi-country programmes still involve coordination) |

| Plan/policy documentation | Employer plan governance and documentation responsibilities can be heavier (jurisdiction-dependent) | Policy contract and endorsements issued by insurer; changes usually at renewal |

| Reporting | Potentially more detailed claims reporting (subject to privacy and data minimisation) | Often higher-level reporting; additional detail may be limited |

| Member experience | Depends heavily on administrator model, network access and case management service levels | Often one insurer-led pathway (service quality can still vary) |

Data and reporting: what you may see, and how to manage confidentiality

Self-funding can provide improved visibility into claims and utilisation patterns, but that increased visibility comes with stronger privacy and governance expectations. Detailed health data is sensitive and may be restricted by data residency, localisation or transfer rules in certain jurisdictions. [11]

GDPR can also be relevant where EU/EEA residents’ personal data is processed, including in benefit administration contexts. Organisations should not assume GDPR does not apply merely because the employer is outside the EU. [12]

- Data minimisation: only request what you need to govern the plan (avoid “nice to have” personal detail).

- Aggregation thresholds: set minimum group sizes for breakouts to reduce re-identification risk.

- Access controls: restrict detailed reports to a small, trained group (HR/benefits + finance where appropriate).

- Cross-border transfers: confirm storage/processing locations and transfer safeguards with suppliers.

- Supplier contracts: ensure the admin contract clearly allocates roles and responsibilities for privacy/security.

Treat reporting as a governance tool, not an end in itself. Overly granular reporting can create privacy risk without improving decisions.

Compliance & regulatory impact

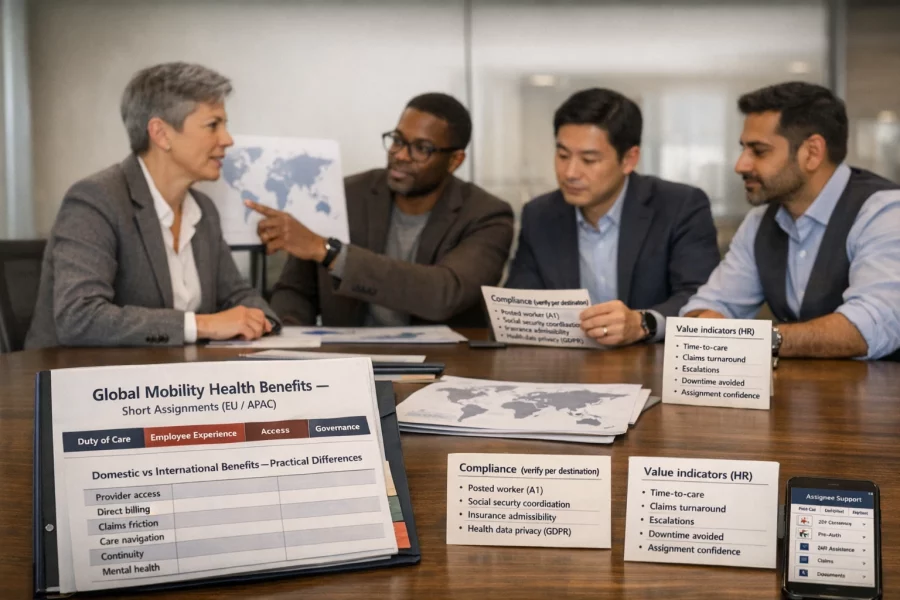

Funding decisions can change your regulatory footprint, especially for multi-country workforces. Three common themes are: (1) insurance distribution/localisation rules; (2) data protection; and (3) specific disclosure expectations in some jurisdictions (including the US).

Insurance distribution and localisation (EU perspective)

In the EU, the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD) sets requirements around how insurance products are designed and distributed, with a focus on consumer protection and governance. [9] In practice, cross-border programmes often still require local review and localisation, because contract law and regulatory expectations can vary between countries. [10]

Data protection and cross-border transfers

Health data is often treated as sensitive/special category data. If your programme involves cross-border processing (for example, an international TPA reporting into a central HR team), you may need to address data residency/localisation constraints and ensure appropriate safeguards for international transfers. [11]

GDPR can apply to processing of EU residents’ data and may affect benefit plans even where the sponsor is outside the EU. [12]

Broker/consultant compensation disclosure (US context)

In the US, the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) introduced compensation disclosure requirements for certain brokers/consultants serving group health plans. Whether this applies to your arrangement depends on plan structure and counsel advice, but where it applies it can place an obligation on plan fiduciaries to obtain and retain disclosures. [13]

ERISA/ACA concepts for expatriate arrangements (high-level)

US-linked international programmes may raise ERISA/ACA questions (including minimum essential coverage and reporting concepts) that depend on plan structure and participant facts. Where US concepts are relevant, treat them as a specialist advice area rather than a “standard global” rule set. [14]

Self-funding may not be permitted or practical in some countries/contexts. Before designing a cross-border programme, verify local rules, licensing/distribution constraints and tax/accounting treatment in each jurisdiction. Where US concepts (e.g. ERISA) are referenced, applicability depends on plan structure and should be confirmed with qualified counsel.

Case examples

These anonymised examples show how HR and benefits teams often approach the decision. They illustrate decision logic — not outcomes — and should not be treated as guarantees.

A 500-employee company self-funds in its home market and values reporting and flexibility. When expanding into new countries, it finds local constraints and chooses locally insured solutions for those populations, coordinated through a pooling structure where appropriate.

- Decision drivers: local permissibility, local delivery capability, and governance practicality.

- Why not “one global plan”: cross-border constraints and operational friction.

A 2,000-employee firm sees meaningful claims volatility and worries about cash-flow shock under self-funding. Stop-loss terms include lasers that materially increase retained exposure, so the firm retains a fully insured approach and focuses on governance and reporting within privacy constraints.

- Decision drivers: volatility tolerance, stop-loss terms, and budget certainty.

- Governance focus: renewal discipline, reporting expectations, supplier oversight.

A 15,000-employee multinational with finance/actuarial depth explores captive-supported structures and selective self-funding where permitted. It invests in compliance, claims governance and data controls before changing funding in any market.

- Decision drivers: scale, governance maturity, and long-term risk strategy.

- Constraint: jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction feasibility and regulator expectations.

A 120-employee start-up wants more predictability than “pure” self-funding but more control than standard insured terms. It explores hybrid options where available and keeps insured cover where local structure makes that the practical route.

- Decision drivers: cash-flow stability, operational capacity, and regulatory perimeter.

- Next step: revisit once claims credibility and internal capability improve.

Case examples are simplified for clarity. Real programmes require detailed plan design, supplier due diligence and local legal review.

Decision checklist

Use the checklist below to structure a benefits committee discussion. The aim is to align funding choice to workforce profile, risk appetite, operational capability and local constraints.

Workforce demographics and size

- How many employees will be covered, and in which countries?

- Is your population large and diverse enough for credible claims projection?

- Are there specific cohorts (e.g. high-risk roles/locations) that could drive volatility?

Risk appetite and financial reserves

- Can the organisation absorb claims volatility without disrupting cash-flow planning?

- Is there agreement on reserve policy and funding mechanics?

- Is predictability (premium stability) more valuable than potential flexibility?

Plan design objectives

- Do you need flexibility to tailor benefits, or are standard insured plan designs sufficient?

- Will additional claims reporting materially change your health management strategy?

Governance and capability

- Do you have (or can you resource) actuarial, legal and compliance support?

- Is HR operations equipped to manage vendor coordination and member queries?

- Do you have a clear claims governance model (decision rights, escalations, audit)?

Regulatory environment

- Is self-funding permitted for the relevant employee populations in each country?

- What distribution/licensing requirements apply to the programme structure?

- What data protection rules apply to reporting and cross-border transfers?

- How do tax/accounting treatments differ between funded models in each jurisdiction?

Stop-loss strategy (if self-funding)

- What specific and aggregate attachment points match your risk appetite?

- Are there exclusions or lasers, and what does that mean in realistic scenarios?

- Does the coverage period align with your plan year and claims payment pattern?

1) Jurisdiction check Is self-funding permitted (and practical) where employees are based? • No / unclear → Start with fully insured (and/or pooling); take local advice. • Yes → Go to step 2. 2) Group size & claims credibility Do you have a sufficiently large group (often ~250+ lives) and credible claims history? • No → Fully insured or hybrid options may fit better. • Yes → Go to step 3. 3) Risk tolerance & reserves Can leadership absorb volatility and fund reserves without creating operational strain? • No → Fully insured is often the safer starting point. • Yes → Go to step 4. 4) Governance & supplier capability Do you have the internal capability (or trusted partners) for claims governance, compliance and reporting? • No → Fully insured/pooling with stronger insurer support. • Yes → Self-funding may be viable; design stop-loss and governance, then stress-test scenarios.

Treat this as a starting direction only. Hybrid structures exist and may be appropriate depending on market availability and local constraints.

Get Started

Choosing a funding approach for international health benefits is usually a governance decision as much as a benefits decision. If you want structured support — including supplier options, programme governance, and cross-border compliance considerations — we can help you map the practical trade-offs and identify a workable structure for your workforce.

Start with our Businesses & Groups page to see how we support employers with international medical programmes. For quick answers to common questions, visit our FAQ.

Further reading: Understanding International Health Insurance (IPMI) and Choosing the Right Insurer for International Health Insurance.

Points to verify

- Whether self-funding is permitted for your employee populations in each target country.

- Stop-loss availability, attachment points, exclusions, lasers, and contract terms.

- Claims administration model (TPA vs insurer ASO) and service scope.

- Required disclosures, remuneration rules, and conflicts management in each jurisdiction.

- Data protection constraints (cross-border transfers, special category health data) and reporting granularity.

- Tax and accounting treatment of funding/benefits in each jurisdiction.

- Pooling/captive feasibility and minimum size/claims credibility requirements.